Luxury brands slow to improve transparency as consumer pressure grows

Simply sign up to the Sustainability myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The environmental charity WWF is set to report that the watch and jewellery industry’s sustainability efforts still leave “much to be desired”, five years after it published a damning report highlighting a lack of transparency.

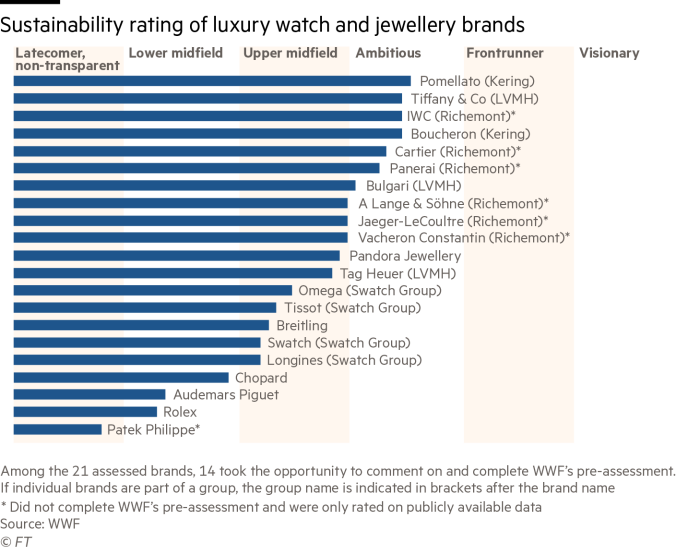

The WWF Watch & Jewellery Rating 2023, due to be published tomorrow, assessed 21 watch and jewellery brands according to their sustainability performance. The companies were judged in nine categories, including sustainability strategy, climate action, human rights and traceability, and transparency.

The report comes as a growing number of luxury watch companies introduce sustainability policies in a bid to increase the desirability of their products. Research such as Deloitte’s Swiss Watch Industry Study 2023 has shown that consumers are increasingly conscious of the impact of their luxury purchases on the environment and society, and that pressure on companies to demonstrate responsible practices is only set to grow.

The impact on the watch industry of a lack of transparency has been brought into sharp focus several times this year — even outside sustainability matters. In June, a record-setting vintage Omega Speedmaster sold at auction in 2021 was revealed to be a composite of more than one watch, leading to claims of fraud and a criminal investigation, which is ongoing. The Only Watch charity auction, originally scheduled to take place earlier this month, was postponed indefinitely after the charity failed to fully disclose its financial position.

The WWF report has been produced, the organisation says, because, like Swiss retail banks, the watch industry is a “relevant driver for environmental change” and that the rating “aims to improve the sustainability performance of watch and jewellery brands by focusing on their global value chain, particularly the sourcing of critical raw materials such as gold”.

In picking the survey participants, the charity says it took a broad view in terms of factors such as geographic footprint and company size, and as such, the report does not offer a comprehensive overview of the industry. Several brands with high-profile sustainability campaigns — such as Oris and Ulysse Nardin — were not assessed by WWF.

The organisation sent a survey of about 50 questions to 21 watch and jewellery brands. Damian Oettli, WWF Switzerland’s head of markets and a co-author of the report, says the brands were selected based on their “revenue, publicity, standing and geographical distribution”. International jewellery brands were assessed for the first time, including Tiffany & Co, owned by the French luxury group LVMH, and Pomellato, owned by Kering.

The six Richemont Group brands rated in the report, including Cartier and IWC, did not respond to the WWF’s survey and were instead rated against publicly available information, such as Richemont’s own annual sustainability reports. All six Richemont brands declined to comment.

“Some companies are very secretive,” says Oettli. “But we’ve seen a shift with this report. Modern leadership values transparency much more highly.”

One such shift came from Rolex, which participated in the latest survey, having previously not commented publicly on its sustainability policies. “Although Rolex still has a number of actions to take, notably in terms of formalising its sustainability policy and codifying its practices, the brand wanted to give an overview via this survey of the state of progress of its sustainability efforts,” Virginie Chevailler-de Meuron, Rolex’s head of public relations, wrote in a statement.

The WWF report gave Rolex a “lower midfield” overall rating, the second-lowest of six in its ranking system. However, in 2018, Rolex was one of eight brands rated as a “latecomer” and “non-transparent”, the lowest rating.

This year, only Patek Philippe was written down with the lowest rating as it neither communicates publicly on its approach to sustainability, nor took part in the WWF’s survey.

Since the report was produced, Rolex has added details of its sustainability policy to its website and introduced what Chevailler-de Meuron described as “an alert system to deal with potential complaints linked to its [Rolex’s] supply chain”. Such systems have already been adopted by LVMH and Kering.

One of the reasons brands may have been more receptive to the WWF’s recent enquiries is the EU’s new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, which came into effect on January 5, requiring many large companies to file reports on their sustainability profile according to European Sustainability Reporting Standards.

William-James Kettlewell, a senior associate at law firm Baker McKenzie in Brussels, says the CSRD will apply to Swiss watch companies if they meet one of a number of conditions scheduled to take effect over the next few years.

“The CSRD could also apply, indirectly, to watch companies headquartered in Switzerland if they consistently generate, at a group level, a turnover of more than €150mn in the EU and have sufficient local presence in the EU,” he said of a condition scheduled to come into force in 2028. The CSRD conditions would oblige most of Switzerland’s major watch companies to report on sustainability.

Aurelia Figueroa, Breitling’s global director of sustainability, also says participation in the report is a sign of transparency. “It’s vital to have an independent external temperature check on how you’re doing,” she says. “Everyone’s coming with a completely different set of criteria according to which they are validating their sustainability performance.”

Breitling was given an “upper midfield” rating by the WWF, indicating the company had identified sustainability issues and was working towards resolving them. Figueroa says since Breitling kick-started its sustainability strategy in 2020 it has put most of its efforts into carbon reduction and has since reduced its “absolute carbon emissions” by around 1,500 tonnes, leaving it exposed when ranked in categories such as biodiversity and water. “We first wanted to get the climate road map in perfect shape,” she says.

On carbon emissions, the WWF report notes that “brands including Audemars Piguet, Chopard, Patek Philippe as well as the Swatch Group brands Omega, Longines, Swatch and Tissot have so far shown little to no effort to reduce their carbon emissions”.

Figueroa says that by March 2026, Breitling will only use artisanal gold and lab-grown diamonds in its watches. “We have explicitly changed some of our supply chains to enable high-quality human rights due diligence, especially for conflict minerals,” she says, adding that Breitling has experienced a “positive” response to its Super Chronomat Origins watch, introduced last year to lead this strategy. “We are seeing quite a bit of pull from the marketplace for these products with sustainability and with traceability attributes.”

Diana Verde Nieto, co-founder of luxury sustainability consultancy Positive Luxury, says it is a shame that brands are being forced by law into this position. “Brands are becoming much more transparent, but they have no choice because of the legislation that’s coming into play,” she says. Verde Nieto is critical of the brands which did not take part in the WWF’s survey. “In today’s world, it feels outdated,” she says. “Maybe it doesn’t matter right now [to sales], but it will matter in the future.”

One of the themes to emerge from the WWF report is the industry’s use of recycled gold. The watch and jewellery industries have not adopted a common definition of recycled gold, meaning gold sold as recycled may never have come into contact with a consumer. Buyers are largely unaware, the report says, that gold labelled as recycled may have been refined from waste virgin material, rather than from post-consumer waste, such as discarded electronics.

In the report, WWF lends its support to a new definition proposed by the Precious Metals Impact Forum, a non-profit based in Switzerland representing the precious metals industry. The definition states that gold should only be qualified as recycled “if it has been extracted from products with a gold content of less than 2 per cent by weight that are destined to be thrown away and returned to a refinery to start a new life”. Otherwise, says the PMIF, gold should be described as “reprocessed” or “reused”.

Sabrina Karib, founder of the PMIF, says the definition could be adopted by organisations such as the Responsible Jewellery Council, which has almost 1,700 members, as soon as early next year. “Most brands would have to rebrand their jewellery as reprocessed and not recycled,” she says. “But I don’t understand why it’s such a big deal, because reprocessed is still very good in terms of circularity.”

According to the World Gold Council, the jewellery sector accounted for almost half the gold mined in 2022. “These brands truly have the power to change the world when it comes to gold,” says Karib.

Oettli agrees, noting that three of the world’s seven largest gold refineries are in Switzerland. “The mining and processing thereof is directly connected to deforestation, soil degradation, water pollution and human rights issues,” he says. “Every second gold mine is located in a forested area (often in tropical regions). Therefore, targeting the watch and jewellery industry, and demanding higher standards for sustainability, is crucial to reducing or mitigating those environmental and social problems.”

In a presentation on its corporate social responsibility performance seen by the Financial Times, Bulgari claims that 95 per cent of the gold it sourced in 2022 for use in its products was recycled, according to the RJC’s current certifications. In the WWF’s report, Bulgari was rated “ambitious”, the third-highest tier. No brand assessed was categorised in the top two tiers.

Antoine Pin, managing director of the company’s watch division, says he would be happy to work with the new definition. “Even if we are not dealing with the appropriate definition of recycled gold, we can still work with our suppliers to go from recycled to reprocessed,” he says.

Pin says he believes the industry is in an exceptional position compared with others because mechanical watches have no inbuilt obsolescence. However, this places a burden of responsibility on it. “We are clearly a luxury item and we can devote some of our costs to improvement, which is not so easy in other industries,” he says. “You would expect a luxury item to lead the pack.”

Moreover, Pin says consumer pressure will drive the industry to become more sustainable. “At some point, everybody will have access to traceability information,” he says. “People will get used to getting this information when buying a product, so eventually, every brand will have to follow this approach. It’s global control by the people.”

At WWF, Oettli says the industry will one day be defined by brands with innovative sustainability strategies. “All business models become obsolete,” he says, referring to the industry’s current sustainability stance. “For a large company, it’s challenging to become something new and adapt to new realities.”

But the industry is moving in the right direction, Oettli says. “We really see sincere movement in the industry and encouraging developments,” he says. “In 2018, there was a lack of understanding, but now even those companies who don’t act have a much more profound understanding of what sustainability is.”

Comments