China grants billions in bailouts as Belt and Road Initiative falters

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

China has significantly expanded its bailout lending as its Belt and Road Initiative blows up following a series of debt write-offs, scandal-ridden projects and allegations of corruption.

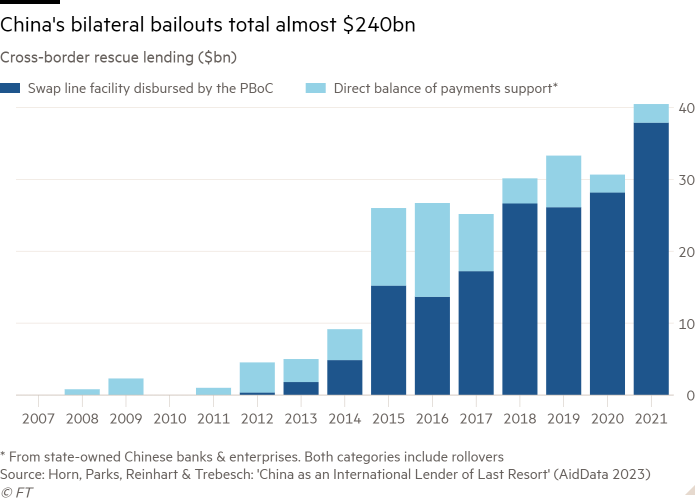

A study published on Tuesday shows China granted $104bn worth of rescue loans to developing countries between 2019 and the end of 2021. The figure for these years is almost as large as the country’s bailout lending over the previous two decades.

The study by researchers at AidData, World Bank, Harvard Kennedy School and Kiel Institute for the World Economy is the first known attempt to capture total Chinese rescue lending on a global basis.

Between 2000 and the end of 2021, China undertook 128 bailout operations in 22 debtor countries worth a total of $240bn.

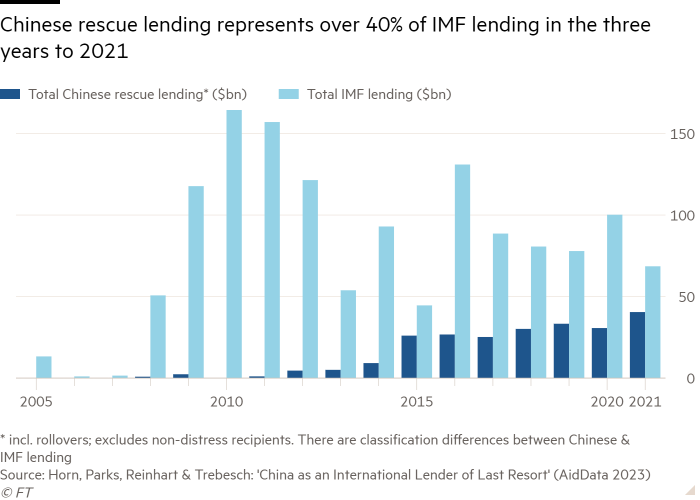

China’s emergence as a highly influential “lender of last resort” presents critical challenges for western-led institutions such as the IMF, which have sought to safeguard global financial stability since the end of the second world war.

“The global financial architecture is becoming less coherent, less institutionalised and less transparent,” said Brad Parks, executive director of AidData at William & Mary in the US. “Beijing has created a new global system for cross-border rescue lending, but it has done so in an opaque and uncoordinated way.”

Rising global interest rates and the strong appreciation of the dollar have raised concerns about the ability of developing countries to repay their creditors. Several sovereigns have run into distress, with a lack of co-ordination among creditors blamed for prolonging some crises.

Sri Lanka’s President Ranil Wickremesinghe called on China and other creditors last week to quickly reach a compromise on debt restructuring after the IMF approved a $3bn four-year lending programme for his nation.

China has declined to participate in multilateral debt resolution programmes even though it is a member of the IMF. Ghana, Pakistan and other troubled debtors that owe large amounts to China are closely watching Sri Lanka’s example.

“[China’s] strictly bilateral approach has made it more difficult to co-ordinate the activities of all major emergency lenders,” said Parks.

Several of the 22 countries to which China has made rescue loans — including Argentina, Belarus, Ecuador, Egypt, Laos, Mongolia, Pakistan, Suriname, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Ukraine and Venezuela — are also recipients of IMF support.

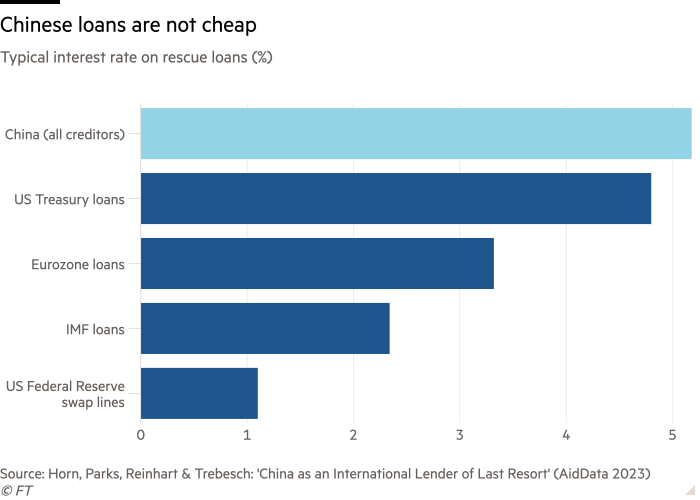

However, there are big differences between IMF programmes and Chinese bailouts. One is that Chinese money is not cheap. “A typical rescue loan from the IMF carries a 2 per cent interest rate,” said the study. “The average interest rate attached to a Chinese rescue loan is 5 per cent.”

Beijing also does not offer bailouts to all Belt and Road borrowers in distress. Big recipients of BRI financing, which represent a significant balance sheet risk for Chinese banks, are more likely to receive emergency aid.

“Beijing is ultimately trying to rescue its own banks. That’s why it has gotten into the risky business of international bailout lending,” said Carmen Reinhart, a Harvard Kennedy School professor and former chief economist at the World Bank Group.

China’s lending comes in two forms. The first is through a “swap line” facility, where renminbi is disbursed by the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, in return for domestic currency. About $170bn was disbursed in this way. The second is through direct balance of payments support, with $70bn pledged, mostly from state-owned Chinese banks.

The BRI is the world’s largest-ever transnational infrastructure programme. The American Enterprise Institute, a Washington-based think-tank, has put the value of China-led infrastructure projects and other transactions classified as “Belt and Road” at $838bn between 2013 and the end of 2021.

The bailout bonanza reveals shortcomings in the design of a scheme described by Chinese leader Xi Jinping as “the project of the century”.

One issue, said Christoph Trebesch of the Kiel Institute, was that Chinese lenders “really went into many countries that turned out to have particularly severe problems”.

Other deficiencies derived from a dearth of feasibility studies and a general lack of transparency, according to the study.

Beijing pushed back on Tuesday against the criticisms of its foreign lending practices, with foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning telling reporters that China had entered financing agreements with developing countries “based on the principles of openness and transparency”. She added that China “has never compelled countries to take its loans, or ever attached political strings to such agreements”.

Several projects became cause célèbre for how not to undertake development lending. An infamous $1bn “road to nowhere” in Montenegro remains unfinished and dogged by corruption allegations, construction delays and environmental issues.

“White elephants” such as Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port and Lotus Tower are seen as symptoms of the country’s debt crisis, while more than 7,000 cracks were found in an Ecuadorean dam built by Chinese contractors near an active volcano.

Additional reporting by Maiqi Ding in Beijing

Comments