The fundamental reason China will struggle to dethrone the dollar

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

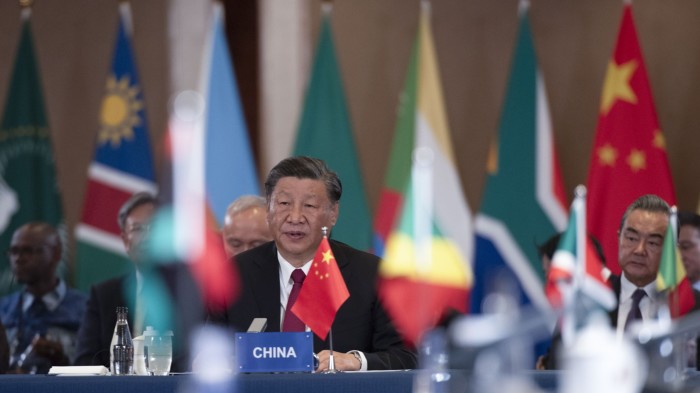

Last week’s Brics summit is disappearing in the rear-view mirror and with it, mercifully, some of the wildly unrealistic discussion of a new currency issued by the grouping’s five emerging market members — aimed at dethroning the dollar.

Policymakers watching challenges to the greenback’s global dominance can return to the more realistic challenge from an existing currency, the Chinese renminbi. While European governments have envied the dollar’s international role since the 1960s and hoped in vain that the euro would supplant it, Beijing’s bid has emerged rapidly and for a more pressing reason, as the US weaponises the dollar. But it will encounter serious difficulties from China’s fundamental problems — which are different from Europe’s traditional weaknesses but, if anything, more deep-seated.

The European desire to challenge the dollar — expressed forcefully in 2010 by Nicolas Sarkozy, then French president, following the global financial crisis — seems largely based on envy of its status as a reserve and trading currency. That role that had survived the final collapse of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system in 1973. The US government and American companies, so European complaints went, could borrow cheaply and avoid exchange rate risk because commodities and other traded goods were priced and invoiced in dollars.

What Sarkozy appeared not to grasp was that, even though the crisis first emerged in the US, it also underlined the indispensability of the dollar as a bank funding and payments currency. Its resilience was underlined by the Federal Reserve’s heroics during the crisis, preventing total global financial seizure by extending swap lines to fellow central banks.

Neither the weak financial regulation that led to the crisis nor persistently eccentric fiscal policy (including self-inflicted debt crises) have destroyed markets’ belief in a currency underpinned by the Fed. Not even the destructive presidency of Donald Trump managed that. Meanwhile, the eurozone government bond market and banking system remain fragmented by national boundaries.

These advantages of the dollar endure. One version of the Brics fairytale is some pitiful rambling from Moscow about the shaky dollar being challenged by a Brics currency backed by gold. But the problems that gold is supposed to solve are absent: the US currency has manifestly not been debased by hyperinflation nor the Fed’s monetary policy independence seriously compromised.

The US policy giving impetus to China’s campaign comes from a different source: the weaponisation of those payments and funding functions to impose sanctions on America’s enemies. When this was limited to the likes of Iran it caused irritation — including to the EU, whose companies were strongly deterred from trading there — but not great alarm.

Now it is spreading to more countries and the US is entertaining far-reaching ideas such as seizing Russia’s central bank reserves to pay for the reconstruction of Ukraine. As my Financial Times colleagues have extensively detailed, more EMs are concerned about relying on the global economy’s dollar-denominated plumbing.

Unlike the euro, which had very few intrinsic advantages over the dollar, China has relatively advanced digital payments systems and can portray the official digital renminbi as a way of skirting US sanctions. But here, too, it hits a problem that the euro has also encountered.

The dollar system is an interlocking set of institutions that it will be hard to replace piecemeal. Cross-border payments can be made in renminbi, but if either end of the transaction ultimately involves a dollar payment, it is still vulnerable to sanctions from the US Treasury. Oil-producing countries may take payment in renminbi, but they are unlikely to want to hold assets in a currency subject to capital controls.

And China would have serious weaknesses as a guardian of the global financial system. The privacy fears around central bank digital currencies can be overblown. But going full-tilt into using a digital renminbi is a leap of faith that the Chinese government, a world expert in snooping, won’t manage to collect and exploit personal data from its users.

Similarly, a hyperactive US administration using American banks to go after Russian oligarchs is one thing. But China imposes broad-ranging trade sanctions on countries — in the case of Australia merely for having the temerity to call for an investigation into the origins of Covid-19.

The roles of an international currency change over time. Yet ultimately, confidence in a global standard involves fundamental trust in its issuer’s openness and reliability.

True, the US willingness to weaponise global networks of payments and other functions, already considerable, will most probably intensify if Trump wins the election. Governments fearing US sanctions might well want to diversify the financial systems they rely on, including towards the renminbi. But China under Xi Jinping is not only seeing its growth model in serious trouble but is moving further towards a repressive state that intervenes extensively in its economy, its citizens’ lives and the security of the region and beyond.

A Brics currency challenging the dollar is a fantasy, but for its part China has self-inflicted problems that will hamper the renminbi’s attempts to take over the US currency’s role on a large scale.

Comments